It’s mid-January as I settle into my desk to confront my bill-paying duties for the month. I go through the routine motions of opening phone, internet, electricity and other bills, noting the amounts so that I can pay them. I come to the email for the natural gas bill from my utility company. Click.

Wait—what’s this?

The amount listed as owing is $666.69. I stare at the number in disbelief, for two rather obvious reasons: For one, it’s a huge amount for a gas bill, higher than I’ve ever seen for this bill in my entire life. And what, for the love of all that is holy, is THAT number doing there?

I’m not scared; I’m not superstitious like that. But now something—or Someone—has my attention.

After several calls to the utility company, I remain as baffled as ever. We’ve just moved to this house a few months earlier, and so far, our utility bills have been higher than expected—but not this high. Sure, December was an extra-cold month here in Vancouver’s Lower Mainland. But this is way out of measure.

All I can get from the customer service rep on the other end of the line at our utility company is that this current bill is about three times as high as the same month for the previous tenants’ bill last year. She doesn’t believe that the December cold snap should account for that much of an increase, citing her own personal heating bill, which only increased by 30—not 300—percent during the same time frame. We know we haven’t been excessive with our heat or hot water usage. What is going on here?

We engage an HVAC specialist to come look at our heating system, in case there is something wrong. He finds nothing out of the ordinary, except an aging heater. Not enough, he says, to account for such a large bill.

We’re tempted to brush it all aside, hoping that our next bills won’t be so high. But they are, and nothing we attempt to do to change it seems to make a difference—turning down the heat, shorter showers, fewer and larger loads of laundry, etc.

But the thing that keeps niggling at me is that number. Why that number, symbolizing evil as it does? The best I can figure is that I’m supposed to pay attention. My intuition is that something unholy—or at least dishonest—is going on. (Dishonesty is unholy, of course, but in popular parlance, ‘unholy’ has taken on a stronger meaning.)

Fast-forward several months, and my husband and I make a discovery: there is a hot water pipe running from beneath a bathtub in our house, through the wall (cleverly covered by a box under a water spigot), down and then underground to a garage nearby that has been converted into a small living unit. We knew the unit was being rented, and had believed our landlord when, in response to our questions, he told us the unit did not use any utilities from our house.

Turns out, he lied.

Just like that $666.69 gas bill was a clue to dig deeper, I sometimes wonder if, as a society, we’re missing the cues to dig deeper into “the Machine” that we experience all around us.

For purposes of brevity, if you’re following this Substack, you may already know what I mean by “the Machine.” Some, like Silicon Valley writer Kevin Kelly, call it the ‘technium’. Others call it the Singularity or the Matrix. But “The Machine” is a term that has been around for quite some time, and refers to the mechanistic world we have created, in all its complexity. It’s that part of human creation that is non-human, increasingly all-encompassing, and threatens to dispossess us of our humanity.

The phrase was introduced by writers such as Jacques Ellul, French philosopher, sociologist and lay theologian, as well as other theologians, from Ivan Illich to G.K. Chesterton. It has since been elaborated on by many writers, including

, who I believe is one of the most cogent (and eloquent) current thinkers on the subject.If you’ve read anything I’ve written here, you’ll know that Kingsnorth’s Machine Essays on his

have had a profound impact on me, articulating as they do things I’d only thought. But there are, in fact, a lot of people writing about this topic on Substack today—or perhaps I’ve just fallen into a deep rabbit hole of them, as Substack suggests accounts to interact with similar to those you already follow.In several online interviews, Kingsnorth has pointed out that there’s a lot of this same kind of “clueing” going on in the realm of the Technium.

Here’s how he puts it in a podcast with Plough Magazine:

“…If you take your iPhone out of your pocket and you look … at the screen, when [it] is off, you’ll see a reflecting mirror.

“It’s almost like a scrying mirror that the old magicians used to look for demons. And you can also see a reflection of your own face. When you turn it on, you get access to all of the world’s knowledge—all of the knowledge of good and evil.”

(As he’s written, Kingsnorth was previously a member of a Wiccan coven, so I’ll take his word on the scrying mirror.)

Not unlike my utility bill story, Kingsnorth further points out:

“When you turn [an iPhone] over, you see a picture of an apple with a bite taken out of it. Now, I’m not sure how much of that is a coincidence, but it’s certainly a pause for thought, especially when you remember that the very first Apple computer, the Apple I, went on sale in 1976 at a retail price of $666.66.

“That is a true fact. I had to double check that, I was so surprised. Maybe it’s all a coincidence or a funny joke, but even if it is, it’s probably worth paying attention to.”

Pay attention

“Even if it is, it’s probably worth paying attention to.” That’s my point—that there may be a reality here that we’ve been avoiding all this time. I call this kind of linguistic clue the “truth on the tongue.” If you listen carefully, people will usually unconsciously tell you what it is you need to be aware of about themselves. Sometimes—as with my utility bill—the warning seems more Divine in origin. In this case, it may be both at the same time.

But we’ll get further into all of this in a minute.

If there’s anyone reading here who is unfamiliar with the potential significance of these symbols, 666 is noted as the “number of the Beast” in the biblical book of Revelation. The symbolic meaning of being marked by this number is that one has chosen false power and false religion over God Himself.

The apple with a bite out of it is a common symbol for original sin, referencing eating the forbidden fruit in the biblical Garden of Eden—the action that caused the ‘fall’ of humankind. (Of course, the Bible doesn’t mention that it was an apple, just a fruit. But popular culture has spread the misconception that the fruit was an apple—just as it has spread the misconception that the first sin was actually the discovery of sexuality. Neither are accurate.)

At this point, I realize the great irony of the fact that I am typing this very article on an Apple computer, and that you may even be reading it on one, via the internet. It’s the overall Machine I’m pointing to here, not a specific brand or technology. My reason for bringing this up is to ask, “Do we need to pay more attention?”

In a short story Kingsnorth wrote in 2020, The Basilisk Revisited, his character asks:

“…What would a demon do if it wanted to enslave you? The answer is... [start] by opening a channel from their world to ours, creating a portal into our lives through which we can be summoned, bound, and ultimately enslaved.

“There is a reason they call it ‘the web,’ …a reason they call it ‘the net.’ It is a trap. We have built the means of our own enslavement, at their suggestion. Now we are all carrying a portal to the underworld in our back pockets and handbags, and we are entirely unguarded against whoever chooses to step through it.”

Since the inception of the Internet, I, too, have wondered about the use of words like “net,” “web,” “webmaster,” mailer-daemon” (demon), and other such lingo. Popular video games in the ‘90s were made by “Wizards of the Coast.” I haven’t kept a complete list, but I suspect readers could add other examples of linguistic clues that might be telling us to pay attention.

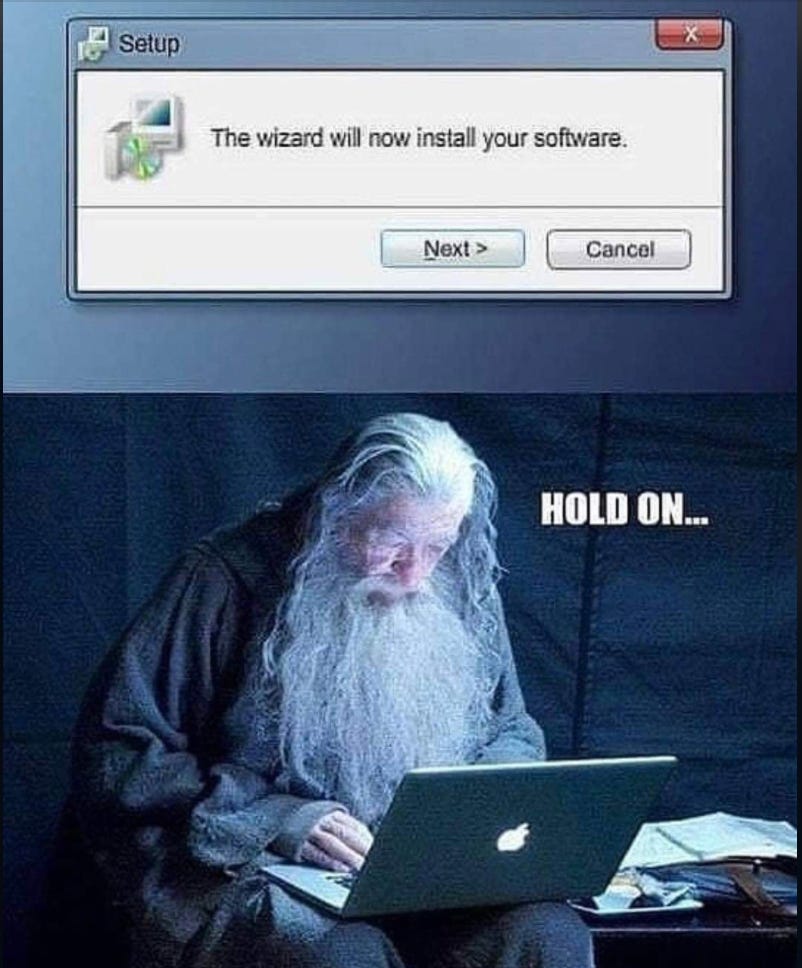

Following in this vein, other organizations have followed suit. “Wizard,” “guru,” “druid,” and other such lingo are now an everyday part of our work vocabulary, coming from the realm of technology, though they obviously originate in ancient religions.

Attention at all costs?

So, what are we to make of these clues embedded into our computer technology from its inception? Is it really just trendy lingo, an in-the-know vibe?

It’s easy to take the point of view that computer and internet technology were developed by a high percentage of people who spent too much time playing things like Dungeons & Dragons; people who had a bent toward the arcane world of fantasy, and who also happened to be quite good at the kind of logic-based thinking required in the world of computing. I personally know more than one software developer who fits this description.

And, it’s possible that this is our answer. We can stop here, laying blame on the eccentricities of the original developer geeks. They were, after all, called geeks1 for a reason—an epithet that formerly had a more negative connotation than it has today.

A more recent line of thinking has given another explanation to this linguistic phenomenon, calling it “criti-hype.” As this narrative goes, technology creators actively fashion the impression that they are ‘evil geniuses’ who need to be regulated, because what they really want is for people to believe that they are geniuses.

Canadian technology journalist Cory Doctorow puts it this way, quoting Facebook investor and board member Peter Thiel: “As … Thiel [says]: ‘I’d rather be seen as evil than incompetent.’ In other words, the operative word in the phrase ‘evil genius’ is ‘genius,’ not ‘evil.’”

A recent member-only event held by The Logic (a Canadian publication on all things Canadian business and tech) raised the criti-hype theory as the reason that so many CEOs of Artificial Intelligence (AI) firms such as OpenAI are currently writing impassioned letters, practically begging authorities to regulate them.

Take for example the 22-word statement Statement on AI Risk from the Center for AI Safety released early summer of 2023, and signed by many of these AI CEOs:

“Mitigating the risk of extinction from AI should be a global priority alongside other societal-scale risks such as pandemics and nuclear war.”

One of The Logic’s journalists, Murad Hemmadi, put it this way: “When you have Sam Altman going to Congress saying, ‘You need to regulate us because we’re so dangerous,’ what he’s really saying is ‘Look at how powerful our tech is.’ It’s fear as a marketing tool.”

Not unlike shock rockers of the ‘80s, this line of thinking goes, technology ‘wizards’ are using (and have been using) shock and fear as a way to market their products. Capitalism 101, right?

Those of a certain era will remember shock rockers like Ozzy Osbourne, who—according to urban legend—bit the heads off live bats in their shows. Did it ever really happen? Nobody seemed to know for many years.

However, in 1982 (the year the concert was held) a fan did come forward, saying that he had brought in a dead, frozen bat and thrown it onstage at an Ozzy Osbourne concert in Des Moines, Iowa. The rocker did indeed pick it up and bite its head off. Osbourne now says he believed it was a fake rubber bat—meaning his instinct to bite its head off was “all for show.”

Either way you cut it with the bat story, shock rockers were embracing a type of criti-hype. Osbourne thought it was a fake bat, but when it turned out to be real, just as well. Attention at all costs, right? Not unlike today’s internet.

Digital media scholar Alfred Hermida, (who was one of my instructors at the University of British Columbia Graduate School of Journalism), in his book Tell Everyone: Why we share and why it matters, has identified six basic emotions that account for the viral success of social media content: anger, disgust, fear, joy, sadness, and surprise.

The success of content that evokes these six emotions accounts in large part for the increasing polarization of our civil discourse—as creators skew their content toward the ever-more inflammatory or outrageous, in order to grab attention and algorithm traction.

But the reality is that these emotions have acted as the sources for human stories long before social media and the internet added speed to the sharing equation. When Osbourne bit the head off the bat in the ‘80s, he was counting on the emotions of disgust and shock to increase his notoriety and popularity.

Evil Geniuses?

My point is not that technology creators are evil geniuses, nor that they are geniuses, nor that they are evil. In fact, my point would be that they are not geniuses and they are also not innocent. In other words, they may be intelligent fools being used by some other “genius” outside of themselves.

While the etymology of genius is from the Latin, which comes from gignere—the same root as we find in “generate” and “Genesis”—rather than from ‘genie’ or ‘jinn’ (demons) as has been at times suggested, it still remains that in the original Latin, one’s genius was considered an attendant spirit, present from birth, that imparted talent.

Tech wizards may have genius in the form of talent and intellect. But intelligence and wisdom are not the same thing. Just because an invention can exist doesn’t mean it should exist. Wisdom is knowing the difference between the two.

Technology’s “evil geniuses” may want to emphasize their genius, but instead, display their lack of wisdom.

Someone may have the intelligence to create a new technology, but that does not mean that what they create ought to exist to facilitate a good and just world. Over the years, some of the creators behind AI, social media algorithms and similar tech, admit that they regret their creations—or at least elements of them.

It is as if, as Kingsnorth and Kelly suggest, something wants to have its embodiment through technology. That seems to be the end-game, where technology is driving humanity toward. That is Kevin Kelly’s conclusion in his book What Technology Wants.

Yet, it seems this “thing” may have been telling us of its existence all along, if only we had ears to listen.

In the same Plough podcast from above, Kingsnorth adds the following:

“If you listen to [Silicon Valley scion and Singularity believer Stewart] Brand and if you listen to all these technologists and transhumanists, they’re all still utopians. That’s the thing that connects them. They all believe that they can use technology to create a completely equal, just world with no suffering and no misery. They’re all trying to immanentize the eschaton. They all want to effectively be gods, but they’ve always got a good argument. They’ll say, “Well, we could end disease. That would be good. We could stop misery, we could stop children dying.” And it’s difficult to argue against it from that materialist perspective.

“So that, I think, is the line. You can use technology to pursue your utopia.”

Doom, Inc.?

In the same Canadian AI panel at The Logic, journalist Claire Brownell shared her discoveries researching her piece, “Doom, Inc.: The well-funded global movement that wants you to fear AI.”

Following the money behind the movements that present AI as scary and downright dangerous, Brownell found that the funding behind each example came from sources that are loosely grouped into the term “TESCREAL.” The term—an acronym coined by philosopher Émile Torres and former Google AI researcher Timnit Gebru—gathers together seven interrelated philosophies: transhumanism, extropianism, singularitarianism, cosmism, rationalism, effective altruism and longtermism.

I won’t take the time to explain all of these philosophies here. Suffice it to say that each of these ideas is purported by—wait for it—Silicon Valley tech gurus, especially those linked to the likes of Ray Kurzweil, Kevin Kelly and others who embrace the “Singularity”—a future moment when humanity and machine intelligences merge, creating in effect, superhumans.

As Brownell explains, “Transhumanists often hold a quasi-religious belief in a coming end time brought on by the singularity, or the merging of human intelligence and artificial superintelligence.”

In other words, what Brownell has revealed is that there is a well-funded internal campaign to hype AI based on its dangerous potential, funded by AI creators and proponents themselves. The message that we should all be afraid of AI is coming from AI backers. It’s criti-hype—using fear to spread the message of the power of AI.

Yet Brownell herself notes that in an opinion piece for The Information, OpenAI investor Vinod Khosla called the firm’s board members adherents to the “religion of ‘effective altruism.’”

She further goes on to describe Sam Altman, former CEO of OpenAI, as “an effusive fan of the now-defunct rationalist blog Slate Star Codex and … one of 25 people who paid US$10,000 to join a waitlist for a transhumanist startup that proposes to euthanize customers and preserve their brains, in the hopes of one day uploading their consciousnesses into the cloud.”

Is this just a banal, man-made religion? Made-up, pie-in-the-sky hopes for transcendence, more palatable to Silicon Valley types because it originates outside the realm of historical religions? Is it amoral and impotent when it comes to the spiritual realm?

These questions lead me to my primary reason for writing this piece.

“Criti-hype” has become yet another reason given to encourage us to shake our heads and ignore the “truth on the tongue” embedded in the language that modern technology uses to describe itself. “It’s just tech companies hyping their tech by creating negative attention,” we’re told.

What if all of these language clues are something we should not ignore? What if these technologies are actually being used by a super-human source—meaning a super-natural source? What if that source cannot help but reveal itself through the very language its creators use to speak about it?

This is a basic question Kingsnorth is raising in much of his work on the Machine. What if, in using these technologies as if they are amoral, we are unwittingly being enslaved by powers outside ourselves? Beyond the dopamine hits and brain chemicals that we’re all aware of, could this be the genesis of what technology addictions, in fact, are?

It should be clear by now that I’m not one who sees a demon behind every bush. What I’m not saying is that people behind technology are all evil servants of the enemy. I’m not saying that they even know they might be participating in this—though some, like Kevin Kelly, are aware because they’re telling us, as he does in What Technology Wants. I’m not saying we should run away from technology.

What I am saying is that we need to have our eyes open and keep them open, and be aware that—like the frog in warm water—we may be getting lulled into accepting something that is, in fact, dangerous. Action on our part to extract ourselves from the technium may at some point be required.

I realize I’ve jumped right into it with this third piece on my Substack. I don’t apologize. These are issues with which we all need to grapple, no matter our faith or non-faith background. So, as always, please know:

Your voice is needed, and we’d love to hear it in the comments below. However, if you choose to abandon the voice of love2 in your comments, remember that you are abandoning all of your beneficial power.

Love is the most powerful force in the universe, alone having the ability to create change for the better. Indeed, it is the only force that ever has.

When I was in elementary school, the kids who played D&D were called ‘geeks’ or ‘nerds’ by other kids. Not kind, but we can see how a possible connection to computer geeks/nerds may have come to exist.

Love doesn’t mean sloppy sentimentalism: love speaks the hard truth, yet considers others before itself.

A banal man-made religion made up of pie-in-the-sky hopes for transcendence by believing that one is "saved" by believing in the "resurrection of Jesus" (whatever that means), and that one will be bodily "resurrected" (whatever that means) when Jesus comes again-seems like a concise description of Christian-ism to me.

Especially the "catholic" version which pretends that it alone provides the whatever for salvation - whatever that means.

Transhumanism obviously sucks but in this time and place one of the last places you find the Truth about the human condition and of Reality Itself is within the walls of the historically dominant world religions, especially Christian-ism, Judaism and Islam-ism