I’ve decided it is time to create a post to explain who I am and why I’ve taken up the pen here on Substack, writing about the influence of the Machine, among other things. I’m hoping that doing so will also be an encouragement to other parents who are trying to raise their children with minimal tech influence.

Those of my subscribers who know me will know that these are issues I’ve been thinking and talking about for quite some time. However, even those who know me may not be aware of some of the crucial parts of the backstory that make me who I am.

To say that I’ve been thinking about issues related to the Machine for most of my life is not an exaggeration. I may not have had the “Machine” as a way to conceptualize it until a dozen or so years ago, thanks to a friend bringing the work of Jacques Ellul to my awareness. Still, I’ve been using a similar framework, without that name, in thinking about these issues.

This stems in part from two foundational experiences that have shaped me. They go together, but the first is the more unusual of the two.

I was one of the rare Gen-Xers who was (gasp!) raised without television during my growing-up years. This was my family’s deliberate choice—not a result of poverty, nor based on a particular religious framework. Yes, for my parents it was a choice they made as Christians because they didn’t want their kids exposed to the negatives and violence of television. But every single other child at the church I grew up in had a television, so it’s not like we were part of some strict sect that eschewed it. It was just my parents’ personal conviction—one for which we kids paid a high price, but from which we also reaped significant benefits.

Parents struggling today to raise kids free from undue Machine influence may find this knowledge helpful.

Throughout my life, I have only known of one other person here in North America who was also raised without television. If my school years are any indication, it was incredibly rare for my generation. More on how this shaped me in a minute, but suffice it to say that, from an early age, I was aware of how my way of thinking was very different from that of my contemporaries and generation as a result.

The Oregon dream, non-Portlandia style

Secondly, growing up as I did in an Oregon state that was, at the time, the “old” Oregon—as opposed to the Portlandia-fied, limp caricature it has now become—we were still living the original Oregon homesteader’s dream, a lifestyle fully embraced by my family.

My father grew up in North Dakota, in a broken family on the run from his abusive, biological father. When my father was small, an Indigenous man (whose name I do not know, but of Mandan Nation heritage) lived with my grandmother and her children for a time. He is the father to one of my aunts. My dad remembers this man spending time with him and showing him how to use a gun, hunt and clean game.

It may be the influence of this man on my father that caused him to, in turn, raise us in a very land-based fashion. We grew much of our own food on our acre of land in Oregon. We travelled around the Pacific Northwest, harvesting fish, clams, oysters, wild blackberries and huckleberries that we preserved. All of my mother’s nearby siblings had gardens and orchards; some also hunted, and we exchanged these various foods with each other.

This lifestyle was once common in Oregon, but when I was growing up on the edge of Portland’s suburbs, my family was somewhat unusual. For a time, my mom even ground her own flour and baked our own bread. However, my parents were not hippies. My father was a full-time special education teacher and did landscaping on the side. My mother was a nurse.

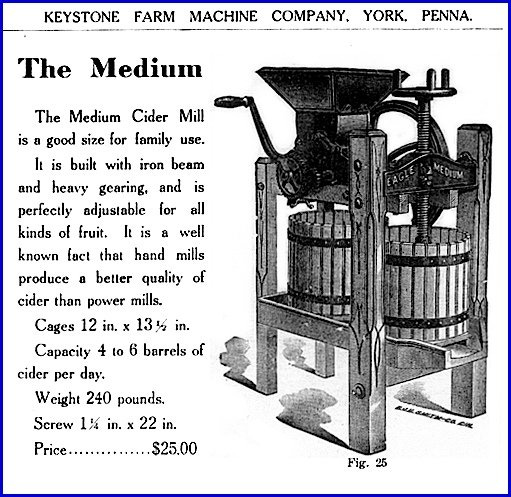

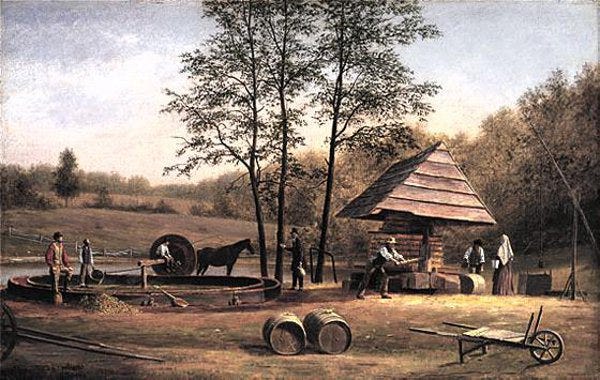

I remember gorgeous, early-fall Saturday mornings, riding with my dad in his sky-blue Ford pickup truck to retrieve a clunky, wooden cider press he had rented. As we road with the back-window open, the wood released its sweet-sour fragrance from a surface stained ochre by the juice of apples. He’d unload it in our church parking lot, where families gathered together with crates of backyard or u-picked apples. We formed an assembly line, cleaning and prepping them, taking them in bowls to the press, where they were dumped and ground. The men would turn the huge cast iron crank, squeezing the press platform and releasing the fragrant juice, which immediately turned a delicious golden hue.

The fragrance was intoxicating—not only to us, but to the bees as well. During the years when we were among the younger kids, I and my friends had the job of scaring away the yellow jackets from the cider press. We did not want them squeezed into the juice or drowned in its vast amber pool before we bottled and froze it in clean plastic milk jugs. Each family went home with enough sweet cider to last them through the winter. It’s one of my happiest, enduring childhood memories. What made it so powerful was the sense of a community coming together to accomplish a task that provided for one another.

Community and togetherness

At other times, my family would gather with relatives and friends to process, can and freeze our produce. I remember happy late summer afternoons sitting outside with my grandma, shelling huge bowls of half-dried “shelly” beans, as we called them. Meanwhile, my brother and dad brought in bushel after bushel of corn from our garden.

When we were finished shelling the smooth and tender beans, my mom would blanch the corn, and it was then my grandma’s and my job to cut it off the husk, running our knife-blade over the severed husks to release the kernel and sweet corn juice that still lay trapped against its surface. It was a sticky job. Afterwards, all of our clothing went straight into the laundry. Every surface in the kitchen had to be wiped down to clear away the starchy spray.

Adding in onion and a few other ingredients, my family made my grandma’s recipe for succotash, an Indigenous food that predates European contact in the Americas. We’d freeze it in Ziploc bags, to be brought out at Thanksgiving, Christmas and other occasions.

As I grew up, this was normal life. At other times, we’d gather snag wood from state forests, my dad covered in the sweet-smelling, white alder chips thrown up into his face and hair by his Stihl chainsaw. I still remember the vrummmm, VRUHMMMMM, bup bup bup bup of the chainsaw as he moved between portions of the downed tree. My brother and I would haul armfuls of logs and stack them into the back of the pickup to take home and season. In the following years, it would be my brother’s and my job to split this wood into firewood for our woodstove with maul and splitting wedge, or axe. The wood partially heated our house, reducing our oil bill.

This woodcutting was often a wet and soggy job, performed on rainy weekends. I remember opening up the steaming Thermos containers full of hot beef barley soup as we sat squashed together in the cab with the rain pounding on the windshield. Have you ever noticed how food tastes incredibly delicious when eaten in fresh air, after hard work? Just one of the many ways we miss out on the fullness of life in our modern, mechanized world.

Have you ever noticed how food tastes incredibly delicious when eaten in fresh air, after hard work?

Needless to say, I grew up a strong and active child. I also read voraciously, easily finishing books in a day. Why not? We didn’t watch TV, so we had all the time in the world.

I realize that all this may have you wondering how old I am, as it may remind you of Little House on the Prairie. Everything I have described here took place in the late 70s and 80s. We were slightly anachronistic, which may have had as much to do with my mom being raised what appears to be a couple of generations off the Amish farm, as it did the land-based influence of my father’s childhood. There is a family tradition that my grandfather on my mom’s side was “Pennsylvania Dutch”—something that, quite late in life, I learned meant Amish.

Early Machine-resistance

I’m sure this land-based, place-rooted life has much to do with the fierce sentiment I felt at a young age to protect ‘nature’, as I called it. In fact, at age eight, I wrote my first environmental activist poem. I’ll spare you most of the cringe-y words of a valiantly-minded child, but it ended with the lines,

“If we do not do what nature has planned, what will become of this beautiful land?”

Still true, still timely—as we see all around us what happens when we do not.

In fact, this fierceness led to my first childhood act of Machine-resistance (and perhaps civil disobedience) as well. When the neighbours sold their back couple of acres adjoining ours, my brother and I were angry to the point of tears. We’d spent many happy days roaming amongst the hay stalks that reached over our heads, tracing the paths of the field mice, exclaiming to one another to “Come see!” whenever we’d find one of their piled stashes of grass seeds stowed away in their little tunnels.

We’d routinely wake to the dewy call of a ring-necked pheasant flushed from those fields by a wandering dog or coyote, the pair startled up with their classic honk-HOONK and audible fluttering of wings. We loved those fields. We didn’t want twenty houses next to our land, with other children running amok in our fields, or watching us in our backyard. At the time, we didn’t see the upside of becoming friends with them, of course.

One day after school, before our mom or dad were home, we went out into the neighbour’s recently-surveyed field, each new lot marked on four corners with surveyor’s stakes. I’m not sure what we thought it would accomplish, but my brother and I quietly pulled up those stakes. All of them—letting them lie where they fell. I think we thought that if we pulled them up, the housing development wouldn’t go forward. We sure showed them! we must have thought. I certainly remember feeling triumphant.

Sadly, it did no good. It may have delayed the process a few weeks, but eventually the houses were built. My brother and I were never found out. Strangely, I never felt badly for doing this. I’m not even sure that I do today—I’m still kind of weirdly proud for having acted on my convictions and stalled the path of the god of Progress, even if just for a time.

How can I tell you that life is just better this way?

This idea that something was desperately wrong in our culture fueled both my interest in other cultures, as well as an eventual focus on Indigenous issues as part of my 2011 graduate school of journalism studies. What fascinated me were the sentiments I was hearing first-hand from local Squamish and other Indigenous Nation members—sentiments that I had previously assumed were only my own, unusual thoughts.

Connection to place

They described a lack of connection to the land that I, too, saw as missing in our culture. That I believed accounted for the wanton destruction of it. I was trying to get to the root of the issue, and I saw this lack of connection to the land as a spiritual issue.

An excerpt from a reflection paper I wrote for my masters-level course and participation in an Indigenous Leadership Forum at the University of Victoria, with Mohawk scholar Taiaiake Alfred:

“I’m interested in the ways in which the Indigenous resurgence movement has parallel movements of shared understanding in settler and even global society. Obviously, movements against globalization share ground with aspects of Indigenous resurgence, as do movements towards food sovereignty. Even the slow food and locavore movements share something at the core: a sense that the society we have created has gone awfully wrong, that we need to re-invent, to perhaps look back to find a way that worked better.

“One need look only to popular culture and films like New World and Avatar (problematic though these expressions are) to know that there is a deep-founded concern that we are wildly off from what it means to have well-being, wholeness, justice and peace with ourselves and the earth—a concept I find best summed up in the original meaning of the Hebrew word shalom. I think this word resonates well with Taiaiake Alfred’s description of “peace” in the opening chapter of Wasáse. Perhaps shalom is a positive concept from some of the roots of settler society that could be pulled into the present to help bridge understanding.

“I see this longing for shalom everywhere. Most recently, I saw it expressed in settler society through the Occupy Movement, flawed though that movement was. The thing is, every human movement is flawed. But we have to do something.”

In short, I’ve long felt that the myth of progress was what was destroying our relationship with the earth, ourselves, others and God. Our shalom.

We’re unnecessarily complicating the good and the simple, exchanging it for the complex and the worse.

This is why I feel a need to point out how much better life is without the layers and layers of technology we create to supposedly give us a better life. Because I’ve lived it.

This isn’t nostalgia, because I’ve always felt this way: that we’re unnecessarily complicating the good and the simple, exchanging it for the complex and the worse.

This also isn’t just an attempt to go back and explain away something difficult in my childhood. Because, I can assure you, we were definitely not the cool kids. Yet, even then I knew that as hard as it was to be different from the other kids—to not know the cool TV shows, the recent phrases, the up-to-the-minute happenings of whatever was the TV show du jour for kids my age, to not know the names of actors and musicians (I still don’t)—my world was deeper, more meaningful and more beautiful without it. Even more importantly, I learned not to care, because I knew I was experiencing something deeper.

How can I tell you that life is just better this way?

I’ve often wondered how I can explain this, when most people probably grew up like the kids around me. How can I share my experience without offending? How can I help you to enter into my understanding, to experience what I see through my eyes?

The coming post-tech renaissance

Yet now, I’m finally starting to see it. Finally. I see people starting to speak about the lack of meaning, the superficiality, the triviality of our Machine world. How they’re drowning in a sea of useless information, and how they don’t like the infantilization of having everything done for them by machines. Last week at SXSW, the premier tech, arts and media festival, the ‘cool kids’ actually booed AI. This news brought me both relief and satisfaction.

Sure, I was a weird kid, but being weird made me able to see. It’s hard to talk about this without sounding better than, but I have to be able to express how I was different. This is my lived experience, and I’ve been discounting it for too long.

How can I tell you that life is just better this way?

Here’s what I was able to observe as a child: Other children had shorter attention spans than I did. This often meant they couldn’t focus or study as well. They seemed to have less capacity for discernment. It appeared that they embraced anything they saw on TV, no matter how stupid, inane or banal. Other children seemed less self-sufficient. They knew less about how to take care of and do real things. Things that would be useful as an adult. They came across as having less capacity for original or inventive thought. Also, they seemed harsher to each other, less caring, less understanding of what the world could be like that would make it good.

Or maybe I was just a serious, different kind of kid. But I don’t think so.

I don’t know how much of this was who I was, how much was my early faith (I came to faith at age seven) and how much was the way I was raised in touch with the land, instead of with technology. I can only tell you what I could see, and why I think things were this way.

Over the years, I have continued without a television or significant media habit, though I do watch good movies and occasionally, limited series. When the internet became popular in the late 1990s, I sensed the lure of opening up email first thing in the morning, something which tended to shift my pattern of morning journaling. This led to me not wanting to be too accessible on smart phone platforms when they first came out. I have never turned on most of my notifications, used Siri, or downloaded very many apps. In fact, my first smart phone was purchased for my master’s in journalism course, and we were asked to install Twitter. I deleted it in 2016, when it was clear that it was becoming a shouting factory.

How can I tell you that life is just better this way?

I was careful with my son’s tech and time spent on tech, which was not popular at times with him. Yet, I saw the benefits as we tried to fill his life with better options. I think he eventually saw it too. As an adult, he’s now buying the classics and reading them. He’s an excellent writer and thinker, likely better than I am, in fact.

I wonder now if the recent spate of “diagnoses” of ADHD in women is due to the damaging effects of the internet and social media on our brains.

After my master’s degree, when I started having to monitor a university’s social media channels for my work role, I felt my brain turning to mush. I couldn’t focus; I was constantly distracted by the notifications, and began forgetting things. Everything. Even pin numbers, phone numbers, past dates, important events, etc. I was no longer meeting all my deadlines because of the lack of focus. It felt like my brain was coming apart.

I wonder now if the recent spate of “diagnoses” of ADHD in women is due to the damaging effects of the internet and social media on our brains. As a child, I’d observed that shorter attention spans and television seemed related. I now think that I was experiencing the beginning of that same problem in this role where I had to spend so much time on social media. I missed my pre-social-media brain.

I couldn’t see an alternative way to make my role at the university work. I couldn’t see a way to both stay there and fix what was happening to my focus. I knew that what I called “the Alternate Life” was the answer (physical activity, growing things, being in touch with the out-of-doors and community). So, I sold my townhome in Vancouver, quit my job, and bought myself a sabbatical so that I could get back into my writing.

It’s taken me eight years, and a lot has happened since then, but here I am, writing for publication again. It’s not perfect and it’s not easy. I certainly haven’t made it all the way to my goal yet: a land-based life connected to a community that would provide a refuge for others and myself in the future. Maybe it’s still coming, I don’t know. The world has changed so quickly in the last four years, the soaring cost of land just one change in many.

And of course, I don’t miss the irony that I’m writing and you’re reading this via the internet. But Substack is by far the best platform for non-destructive communication I’ve found, and we need to hear each other.

How can I tell you that life is just better this way?

Your voice is needed, and we’d love to hear it in the comments below. However, if you choose to abandon the voice of love in your comments, remember that you are abandoning all of your beneficial power.

Love is the most powerful force in the universe, alone having the ability to create change for the better. Indeed, it is the only force that ever has.

Hey there— I’m here via Paul Kinsgnorth’s recommendation. I’m another tv free kid! I grew up on a small Indiana farm in the 80s and 90s without a tv, homeschooled with my brother, with both sets of grandparents and aunts, uncles, and cousins within a 1-15 minute drive from our home. I can relate to many activities you’ve shared here.

My brother was my best friend and we are still close. We played outside all day every day in the summer, accompanied our dad and grandpa as they worked on the farm, I read a lot (or our mom read aloud to us), and we also spent plenty of time in our other grandparents' woods. (Incidentally, as adults we have both chosen to build homes in those woods, and our families each live a one-minute walk from our 88 year-old granny’s front door.)

At some point in my childhood, we did acquire a tv and VCR, but it was kept on a cumbersome old cart in the hall closet, which we had to pull out and navigate through the house if we wanted to watch a movie— the inconvenience was a built-in deterrent.

My husband (raised with tv) and I have chosen to remain tv free for the most part. I say for the most part because we began using our laptops to watch DVDs many years ago, and just in the last year have gained access to fast enough internet to begin streaming shows and movies. Our 17 year-old son recently acquired a tv that is the focal point of our living room, but when he moves on, my husband and I have agreed to just keep using a laptop if we want to watch something. It’s a little small, and a little inconvenient to set on the ottoman in front of the couch or plug in mid-show if the battery is low— but I like that about it.

Both myself (a Millennial) and my husband (Gen X) were raised without a TV. And yes, we were very out-of-touch with everything our peers were talking about. But it was everything you described here. We now have been married nearly two decades and have never had a TV (still!). It still makes us weird, but we’re okay with it.